School Desegregation Position Of The Oktibbeha County Branch- NAACP

The Process of Desegregation in Oktibbeha County

In 1954, the supreme court Brown v. The Board of Education ruled that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional , this decision overturned the landmark “separate but equal” which was a doctrine that had been in place since 1896. This ruling had a huge impact for schools of educational facilities who had no place in the field of public education , in which it ended legal segregation in public schools, which led to more integrated schools but the school board of Starkville and Oktibbeha have operated” outside of the law of the land.”. Dr. Douglas L. Connor in his autobiography. A Black Physician Story: Bringing Hope in Mississippi highlights the struggles and challenges black people had to face to make a change to the system that marginalized them. The desegregation of Oktibbeha County was one of those challenges in which in the article written by the Oktibbeha County Branch NAACP and also civil rights activist who took part in this battle for desegregation in which they had plans to do the desegregation since the plans they adopted didn’t meet the approval of half of the black community in which they put out a statement saying “Separate schools for the races in our city and county have resulted in inadequate preparation of our young people-black and white- to meet the needs and challenges of life in America and the world today.” (NAACP 3).

This statement highlights the important focus of this segment was education and how they wanted Black people to have the correct education to fight racial segregation and inequality, and to ensure equal access to education for all. The process of desegregation was a back and forth thing with the court and the NAACP with the court saying that the NAACP fails to see the vision of separating a school into the city and county, this response led the NAACP opposing the idea of closing any school base on race because it will be a waste of taxpayer money. Especially if the taxpayers wanted to pay for the proper education for the children. After months going back and forth there was a court order in 1970 to end desegregation from Oktibbeha County and public schools which marked a huge change in history.

Desegregation in Public Schools

The desegregation of public schools was a huge success but it didn’t come with some drawbacks even after the court ruled that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional but even then schools never really integrated in the document School Desegregation Position of the Oktibbeha County Branch- NAACP highlights this separation in which “The schools of Starkville and Oktibbeha county are still, for the most part, all white or all black. There is no question that most of the money spent for education in the city and county goes to the nearly all-white schools. Disadvantaged children who suffer the most are provided the least of educational opportunities.” (NAACP 1). The NAACP discussed this in the article because they couldn’t stress it enough that the schools are not integrating because money is being sent to other schools instead of helping the people of least educational opportunities to further the integrating process.

This dives into how public schools faced deliberately challenging process where a lot of people actively resisted integration through legal maneuvers and intimidation tactics. For more than a decade, there were plans which allowed white families to keep their children in all-white schools while discouraging Black students to not transfer base off violence and sending them really hateful letters. This lead to black families who applied to white schools faced threats and intimidation which forge the plan of “Freedom Of Choice” which gave students the freedom to choose their schools, it intended the integration of the public schools because White people did not attend all black schools and Black people did not attend all white schools. The federal government came in and threatened to cut off all federal funds, and then the schools board promise to work on a new long-range plan, which didn’t come into favor because federal officials were not impressed which led them to cut off funds to the school district on September 13, 1968. (Connor and Marszalek 151).

BENEATH THE QUIET SURFACE , HOWEVER, THINGS WERE STARTING TO HAPPEN

DOUGLAS L. CONNOR

Dual School System In Starkville and Oktibbeha County

Before 1970, Starkville and Oktibbeha County operated a dual system that segregated students by race. Black students attended the Oktibbeha County School Training School, later renamed Henderson High School, while white students attended the better funded Starkville High School. This segregation extended beyond student bodies to include disparities in resource and facilities. In 1969, as federal mandates for integration loomed, white families established Starkville Academy, a private institution designed to maintain segregated education. The Oktibbeha County Branch of the National Association For The Advancement of Colored People stated in the document of the school desgregation position stated “Is very much in favor of a will insist on complete and speedy elimination of the school dual systems In Starkville and Oktibbeha County. Since nearly four hundred students living outside of the Starkville Seperate School District attend Schools within the city limits,” (NAACP 2)

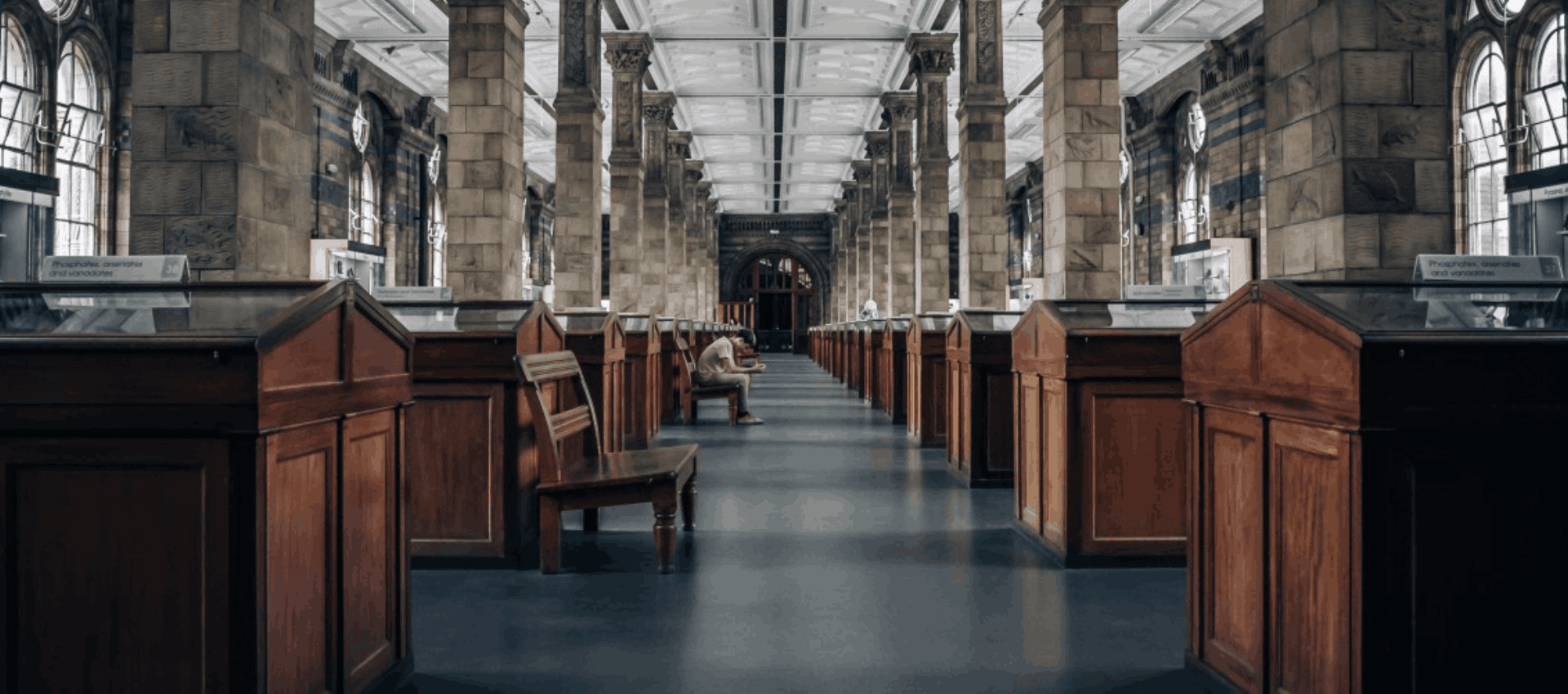

A True Certified Copy of the NAACP School desgregation position of Oktibbeha County. Special Collections Department, Misssissippi State University Libraries.

Looking further into this document we see that the dual school system in Starkville and Oktibbeha County was criticized for perpetuating racial inequalities and failing to embrace the vision of integrated education. As stated in the document “The NAACP fails to see the wisdom of separating a school desgregation suit into city and county – especially since the board has no intention of excluding students from outside the district now or in the future.” (NAACP 2).

To those among you who think that white is always right- the Uncle Tom’s, Uncle Remuses, the Aunt Jemimas and all of the brain washed Blacks-we admonish you now to get out of our way to step aside- to make way for proud Blacks who are not ashamed of their races or color- to make way for the new spirit of Black pride, Black Power and Black Awareness that will one day make us Free!

Douglas L. Connor

The NAACP plans for desgregation and the integration process

A True Certified Copy of the NAACP School desgregation position of Oktibbeha County Continued. Special Collections Department, Misssissippi State University Libraries.

This document discusses the plans for desegregation which was a complicated process. This process had resistance to the integration remained strong, through legal action, advocacy, and community organizing, the NAACP challenged the slow, token efforts of local school districts that sought to maintain segregation under the plan of “Freedom of choice”. By the late 1960s, with federal court rulings such as Alexander v. Holmes County demanding immediate compliance, the NAACP intensified its efforts, pushing for court-enforced desgregation plans that would ensure Black students had access to the same equality of education as their white peers. As discussed in this document “Separate schools for the races in our city and county have resulted in Inadequate preparation of our young people- black and white- to meet the needs and challenges of life in America and the world today.” (NAACP 3).

While doing this, the organization not only fought against segregation but also the against the deeply embedded structural inequities that local government sought to preserve, emphasizing that true desgregation required more than just allowing Black students into white schools- it required the an unique redistribution of resources, opportunities, and power within the education systems. After public schools were legally desegregated, Black children seemed to be treated fairly in the public schools but it would lead to many more stuff happening like white families withdrawing their kids and heading to a more private segregation academy like Starkville academy. Despite legal desgregation, many public schools remained segregated in practice due to residential patterns and continued inequities in funding, teacher distribution, and academic opportunities. While the public school integration process was a legal victory, the struggle for equal educational access and resources continued long after court-ordered desegregation. “To my way of thinking, blatant racism was the reason for the establishment of the academy in Starkville.” (Connor and Marszalek 156)

Other Schools in Mississippi that got desgregated

While schools in Starkville and Oktibbeha County was getting desegregated there was also a county named Yalobusha who mirrored the same struggles faced following the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954. Many people still rejected the integration process which in response to federal mandates, private segregation academies to circumvent desgregation. There was a boycott in the community to pressure the school boards to degregate the schools. It was organize by the civil rights movement members which they pushed for immediate and full desgregation, often facing violence and economic retaliation for their efforts. The Civil Rights Movement’s fight for equal schooling was not just about integration but about ensuring quality education for all students, a struggle that continues today. The transition to having white children and Black children in the same schools for the first time in history wasn’t an easy one- for Black children or for Black teachers in Yalobusha County.

Overall, desgregating public schools in Starkville, Oktibbeha County, and Yalobusha County was not a smooth process, but a recursive process involving a lot of plans, protest, court orders, and a lot of time for years. Children from both races in starkville began schooling together after schools were legally desegregated but took some time to get to that point.

Works Cited

Connor Douglas L and John F Marszelek. A Black Physican’s Story: Bringing Hope In Mississippi. University Press of Mississippi 1985

Connor, Douglas L. Legal Material, Document File, NACCP., Box 2 Folder 3. Special Collection Department, Mississippi State University Libraries.

Brown, Brittany. “Life is different here than it was when I grew up’: The legacy of schools segregation in Yalobusha County.”https://mississippitoday.org/2021/02/12/legacy-of-school-segregation-in-yalobusha-county-black-history-month/. Accessed on 7 Mar. 2025.

Leave a Reply